So you wanna be a Tonal Director

In the typical organ company, the Tonal Director is someone who is head of sales, and draws up stoplists according to what the market can bear. However, he also has other important things he should consider.

The organ's loudness should match the church. It must be capable of leading full congregational singing, even if the building is large and acoustically dead. But it shouldn't overwhelm the room, scaring the old ladies. The organ also needs some softer voices to balance a timid singer, or quiet parts of the service. He needs to know how to measure the room and it's acoustics, to determine the loudness needed. A good tonal director knows how to set appropiate wind pressures, and scale and voice the pipes, to get the loudness right.

Besides service playing, the tonal director should be able to play the repertoire. He should be an organist and understand traditional French, German and English organs and their music. Not to build historic copies, but so he is able to build his organs so that music works on them. He should visit traditional organs, or at least listen to authentic recordings of them, and study their construction, scales and voicing.

I'm no Tonal Director. But I have worked for several fine builders, and had my own workshop for about 40 years. I've worked on a lot of organs and voiced, tonally finished, and rebuilt/revoiced a bunch. I've developed with some ideas and tools that could be useful to you. And I have a large library of historic and contemporary pipe scales. This website is a work in progress. I have a lot of material, which is constantly being added, so keep checking back! I'm not a scholar or historian. These are just my personal notes, gathered over a lifetime; so don't expect them to be properly referenced or attributed.

There are three great schools of organbuilding:

- The German Baroque polyphonic school (e.g. Schnitger [1648-1719], Gottfried Silbermann [1683–1753]) with composers like Bach.

- The French Romantic, Symphonic School (e.g. Cavaille-Coll [1811-1899]) with composers like Frank and Widor.

- The Romantic English School (e.g. Willis [1821-1901], Wm Hill [1789-1870]) which accompanied massed hymn singing and English Choral tradition.

Of course, each school influenced the others. Contemporary organbuilding is profoundly influenced by the three schools. As North America was an English colony, North American organbuilding was based on English traitions. But modern builders use choruses based on German Baroque methods. They borrow mutations, cornets and reed from the Classical French. The French Symphonic school contributes excellent strings, Harmonic Flutes and new ways of building choruses. So you need to know about them.

I'm not advocating eclectic organs, assembled from a Potpourri of stops. The most successful instruments embrace one style, though they may judiciously poach good ideas from other schools.

I start with a small booklet describing how pipes work, what scales are, their history, how to lay them out, how to plot them on a graph, and about Topfer. Then we look at how to adjust the loudness of organs to match the size and acoustics of the church. Next we look at some specialised organs: box organs, miniature organs and practice machines, which require special scales and voicing. We look at a bunch of historical and modern example organs, giving some scales and voicing measurements. Finally, we look at some suggestions for rebuilding and revoicing existing organs.

A list of topics:- Introduction to Pipe Scales: history, measuring, graphing and usage

- Acoustics and loudness

- Specialised small organs & scales: miniature, box organs, practice machines

- Dutch/North German early organs

- North German Organs: Arp Schnitger

- Central German Organs: Gottfried Silbermann

- French Organs, My Book and Classical

- French Organs, Andreas Silberman

- French Organs, Cavaille-Coll

- English Organs, History and scales

- Contemporary organs

- Rebuilding organs

Introduction to Scaling my book

This PDF is some of my personal notes about the measurements of organ pipes. Bigger pipes are louder and duller. If you know the size of the pipes you can understand what they sound like, and use those measurements to make similar pipes.

I describe the history of pipe scales and the ways they can be laid out. I also describe how you can represent them on graph paper and analyze what they must sound like. I also go into the theory of how pipes work.

There are many excellent experiments and research into the physics of organ pipes (see below). Unfortunately, when the earliest researchers described what they think is going on, they got some of it wrong. Then later researchers cling to past ideas; there are hazards to conducting liturature searches.

So, how do pipes actually work? There are a number of theories. The original theory of Vortexes has been mostly rejected. The difficulty for most theories, is the theory's inability to explain how the cutup affects the tone. I would suggest a combination of "Standing Wave Feedback" for the fundamentals and "Edgetone theory" for the overtones and brightness is plausible. Some theories:

- 1) Vortex theory

- 2) Areo reed

- 3) Edgetone Theory

- 4) Standing wave feedback loop

- Boner, C.P. - Acoustic Spectra of Organ Pipes, 1937 (I don't have...)

- Meyer, Jürgen - Resonanz and Einschwingvorgange Labialer Orgelpfeifen, 1960 (I don't have...)

- Nolle, A.W. - Some Voicing adjustments of flue organ pipes, 1979 (I don't have...)

- Sundberg, Av Johan - Mensurens betydelse i oppna labialpipor, 1966 w/english summary (I don't have...)

- Coltman - Sounding Mechanism of Flute and organ pipes, 1968

- Ising, Dr Ing. - Erforschung und Planung des Orgelklanges (Exploration and planning of organ sound) - Walcker Hausmitteilung Nr. 42, 1971

- Coltman - Jet drive mechanism in edge tones and organ pipes, 1976

- Fletcher, Neville - The Physics of Organ Pipes, 1983

- Fletcher, Neville - The Physics of Musical Instruments - Ch 17, Pipe Organs 1991

- Rioux, Vincent - Sound Quality of Flue Organ Pipes, 2001

- Steenbrugge - Aerodynamics of flue organ pipe voicing, 2010

- Angster, Judit - Acoustics of Organ Pipes and Future Trends in the Research, 2017

- Yoshikawa - Vortices on Sound Generation and Dissipation in Musical Flue Instruments, 2019

- Díaz, Óscar Martínez - Aeroacoustic characterization of a 3D organ pipe, 2022

- Liljencrants, John - End Correction at a Flue Pipe Mouth, 2006

- How the Flue Pipe Speaks - Colin Pykett

The Room, acoustics & loudness

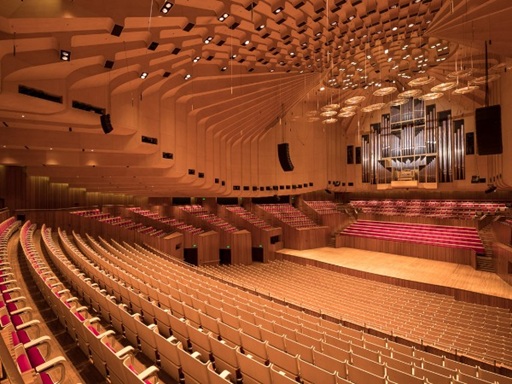

Churches come in all sorts of sizes, and one of the challenges to organbuilding is to match the loudness of the organ to the room. Each room has it's own size and reverberation, which affect the organ. A bigger room requires a louder organ, with larger scales, louder voicing and higher wind pressure to adequately fill it with music.

However, a big part of acoustics is reverberation. Reverb is how a sound persists in a room by bouncing off hard reflective surfaces. Reverberation adds to the direct sound, making the organ louder. So, a bigger room makes the organ sound softer, but reverberation makes the organ louder.

Reverb makes organs sound better; the more the better. However organbuilders have little control over improving reverberation; we can try to persuade the church to remove some of the carpet... However, we can calculate the effect of the room volume and reverberation, and use those numbers to guide organbuilding.

Specialized Organs, small is beautiful

Box Organs

To my mind, a box organ has a special purpose, to accompany or play with a chamber orchestra and/or choir. To do this it must meet specific, often conflicting requirements.

Many of the box organ designs are too bulky and require a truck and four strong men to move. Or they are built tall, like a positiv and block the view. Or they use miniature pipes that are voiced too weakly to be heard doing battle with a chamber group.

Miniature Organs

A church is a large building and requires a powerful musical instrument, such as a pipe organ, that can generate enough musical power to lead massed voices in hymn singing. As well, the organ must have sufficient power to fill the room when playing the organ liturature. But if you move a church organ into a home or practice studio, the pipework and voicing would overwhelm the listener. It would be too darn loud!

At Brunzema's we developed a series of small organs, using special scales and voicing, suitable for smaller spaces. As Brunzema has been dead for 40 years, the firm had no successor, and I was involved with them, I see no harm is sharing some things about them, and the box organ here. The size of these organs was determined by constraints: height by a typical home ceiling, width by the pedalboard, and depth by passage thru a typical room doorway. To save space, the two 8' stops and the pedal 16' shared 17 offset pipes. Space determined the stoplist, explaining the 2-2/3' tg, 2', 1-1/3, 1' stops.

The standardized case split into three horizontal sections, so to fit thru a doorway. The middle section has the keyboards, chests, key and stop action which could be shipped pre-assembled.

Practice Machines

Practice machines present special problems. They must be compact, and soft enough to be played in a small practice studio, for long periods of time. They require two standard, full compass keyboards, plus a standard pedalboard and three couplers: Sw-Gt, Sw-Ped and Gt-Ped. Each keyboard requires at least one independent sound, so you have a minumum of three stops.

However such a minimalist organ is a poor investment. You've paid for two keyboards and a pedalboard, plus the complete actions, chests, wind system, and casework, but you can only use it to practice fingering. It would be better to invest in a few more stops, so that you can actually make music with the organ.

Dutch/North German early organs

I spend several summers organcrawling northern Europe about 1979. I took lots of photos, some of which are shown below. Fortunately the North European Organ has been extensively studied and there are many good books available for you to study.

The pipework of several important organs have also been scaled and shared below. I don't know who did the measuring, nor do I remember who sent it to me.

There are some interesting North German organs from the 16th and 17th centuries that still exist in playing condition. However, they have all been reworked and rebuilt over and over again. Some of the pipework is likely recycled from even older organs, so it is difficult to be sure from existing examples, what an early organ was really like. You have to be sceptical of the scales and voicing.

Hillerod is a virgin, but it is a freak organ built for secular purposes for a Royal castle. It is built using unusual materials (ivory and ebony) and all the pipework is wooden. (Photo is the 1624 Scherer-Organ in Tangermuende, Germany.)

German Organbuilding Files- List from 1970's of Historic North European Organs

- Structure of the North German Organ - Harold Vogel

- Oosthuisen 1521 - Church history

- Oosthuisen 1521 - Chest details 1974

- Oosthuisen 1521 - Casework mouldings

- Oosthuisen 1521 - Scales Fisk 1974

- Oosthuisen 1521 - Scales, Flentrop, graphed

- Alkmaar, Grote Kerk, Small organ

- Alkmaar, Grote Kerk, Small organ, scales 1

- Alkmaar, Grote Kerk, Small organ, scales 2

- Alkmaar, Grote Kerk, Small organ, scales 3

- Hillerod, Compenius Organ - Drawings and scales

- Kreward, History

- Kreward organ scales - from John Brombaugh

North German Organs Arp Schnitger

By the end of the 17th century, North German/Dutch organs developed a consistant style of playing, sound, stoplist, casework (the Hamburg case), best exemplified by Arp Schnitger (1648–1719). Schnitger built in a conservative, traditional, almost backwards looking style of organ, that consolidated and summed up Baroque organbuilding. He is important because so many of his organs survive.

Arp Schnitger (1648-1719) was the idol of the Orgelbewegung. His scaling was very inconsistent between organs, and even within the same organ. This was partly because he enthusiastically recycled pipework from previous instruments. This recycled pipework was very compatible with Schnitger's style of building. Also, Schnitger had the monopoly on organbuilding in the region, so other organbuilders had to work under him as subcontractors, who brought their own methods. And, I suspect pipe scaling wasn't particularly important to him, he could work with what he got. He doesn't seem to be following any mathematical, geometrical, proportional, logrithmetic or additive scaling system.

However, people who enjoy analyzing pipe scales, find Schnitger's organs very frustrating. Certainly the general concepts are correct: a Quintatena is a narrow stopped pipe with low cutups; a Gedackt is a fat stopped pipe with high cutups. But Schnitger Gedackts, for example, can look very different from organ to organ, and even within an organ, for no apparent reason, while still being a Gedackt. When studing his instruments, it is better to step back and look at the big picture, and not get stuck on the details.

The Neo-baroque organbuilders were inspired by what they read of Schnitger. However, when you play a typical chiffy neobaroque organ, with low cutups and narrow flues, one wonders how many of them had actually seen or played a Schnitger? The Neo-baroquists built some wonderful organs, but few would be confused with one of Arp's.

Photo is the Arp Schnitger 1698 organ (typical Hamburg case) in Reformed Church Pieterburen (Groningen).

Arp Schnitger Files- Alkmaar, St Laurenskerk - History

- Alkmaar, St Laurenskerk - scales 1

- Alkmaar, St Laurenskerk - scales 2

- Alkmaar, St Laurenskerk - scales 3

- Alkmaar, St Laurenskerk - scales - Gr & Chor

- Altenbruch, St. Nikolai

- Cappel, St Johannis-Kloster

- Cappel, St Petri & Pauli - Organ study

- Hollern, 1692

- Ludingworth, Wilde-1597, Schnitger-1681.pdf

- Mittelnkirchen

- Mittelnkirchen Scale Graphs

- Nieuw-Scheemda - world's loudest, smallest Schnitger

- Neuenfelde Stoplist, Arp Schnitger, 1696

- Neuenfelde Scales, Arp Schnitger, 1696

- Norden 168?

- Steinkirchen, 1682 - data from Orgues Historiques

- Steinkirchen, scales

- Steinkirchen, Gt scale graphs

- Steinkirchen, Reeds, 1682

- Marienhafe, Ostfreisland, baroque organ - (not Schnitger, but simular)

German Organbuilding Gottfried Silbermann

A generation later, Gottfried Silbermann (1683–1753) was building organs that consolidated German and French ideas. He was building an organ looking away from the early Baroque and toward the future, even hinting at Romantic ideas. He never recycled old pipework as it wasn't compatible with his organs, and kept tight personal control over the design of his instruments. The stoplists, casework, voicing and scaling were very consistant from organ to organ.

Because so many Silbermann organs have survived to the present, have a uniformity of design, and are simular to modern American-Classic organs, Gottfried's organs were greatly admired and copied by builders like Larry Phelps. Indeed, add a Gamba and Celeste to a Silberman and you get a stoplist that could easily be confused with a modern organ.

Notice that the central German organ casework is styled differently that the Schnitger North German cases.

(Photo is Frankenstein, Dorfkirche, Sachsen, Germany - Gottfried Silbermann 1753.)

Gottfried Silbermann Files

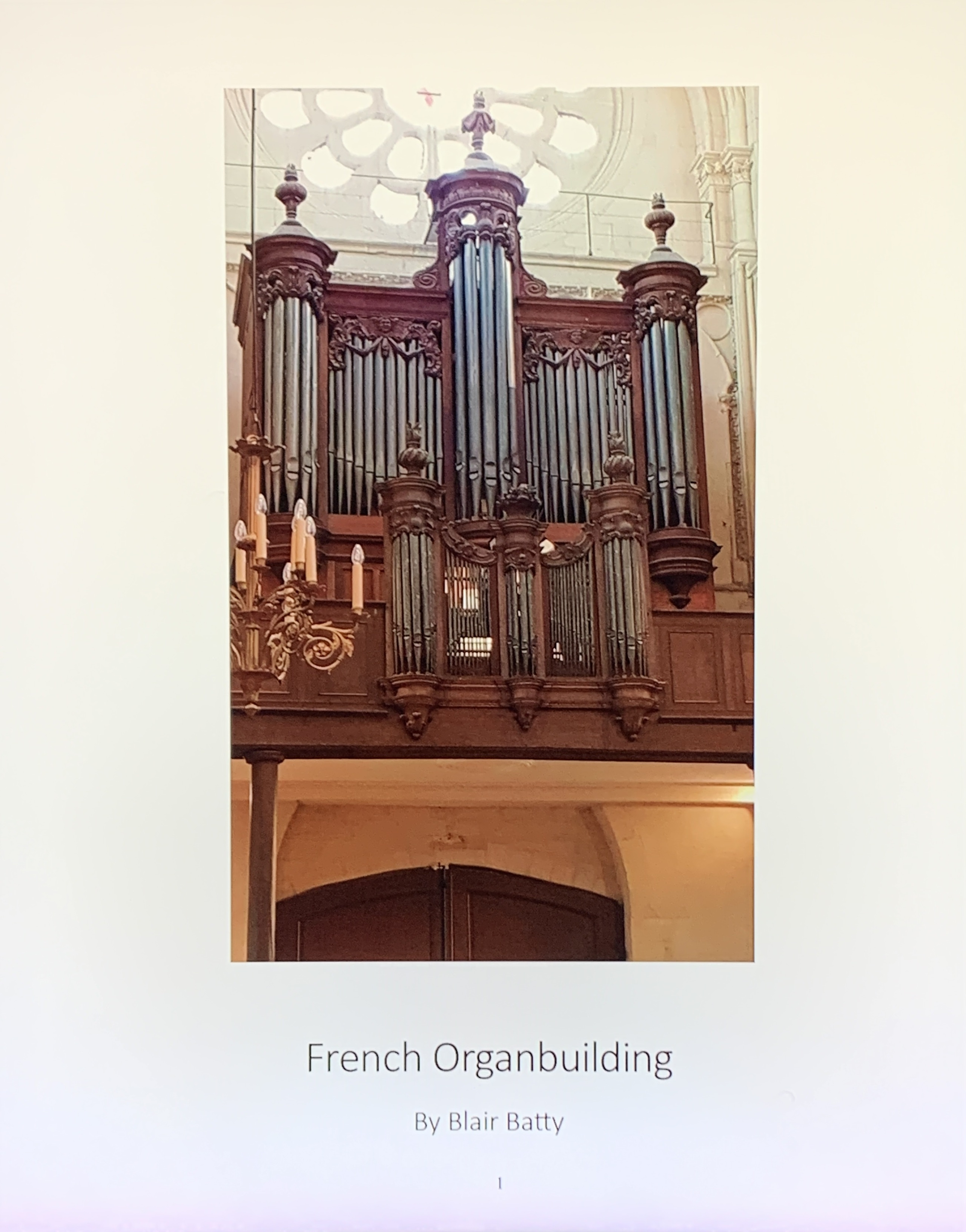

French Organbuilding my book

Except for some Andreas Silbermann organs in the Alsace, I have never seen or played a French organ. So it seemed quite logical to write a book about them. I have done some reading about Dom Bedos and Cavaille-Coll and looked in to their pipe scaling methods a bit, so here are my notes about that.

French Organbuilding Andreas Silbermann

Andreas Silbermann (1678–1734) was a highly influential French organ builder of the late Baroque period, and a central figure in the famous Silbermann family of organ builders. He was the older brother of Gottfried Silbermann (1683–1753), who became even more famous. The brothers learned organ building in Alsace (then part of the Holy Roman Empire, now France) from another important builder, Andreas’s brother-in-law, Johann Friedrich Wender, and were also influenced by French organ building traditions.

Andreas settled in Strasbourg (in present-day France) and built organs mainly in the Alsace region, as well as parts of southwestern Germany. His organs were known for their clear, balanced tone, fine craftsmanship, and incorporation of French classical organ features (reeds, mutations) into German liturgical music needs. He built about 30 organs, many of which survive in restored or partially original condition. Today, Andreas is seen as the founder of the Alsace branch of Silbermann organ building, while Gottfried led the Saxon branch blending German and French aesthetics.

Andreas younger brother, Gottfried Silbermann, was forced to flee to Germany to excape prison after a scandel. In Germany he build French organs with a strong German accent. Gottfried worked in Saxony and became the preferred builder for J.S. Bach’s circle, with a somewhat different tonal style (more German Baroque, influenced by central German traditions).

- Andreas Silbermann (1678-1734)

- Gottfried Silbermann (1683-1753)

- Johann Andreas Silbermann (1712-1783), son of Andreas

Andreas' son Johann Andreas Silbermann (1712–1783) inherited the Strasbourg workshop and documented many Alsace organs in detailed organ surveys. He continued his father's Alsatian style but was also influenced by his uncle Gottfried's Saxony German accent. He worked primarily in Alsace (now France). He was known for his meticulous craftsmanship, elegant cases, and a sound that blends French elegance with German solidity. Johann Andreas adapted German scaling for his principals, while continuing French scales for Flutes and Mutations. However, Gottfried Silberman continued using French scales.

Notable Surviving Andreas Organs

Notable Surviving Johann Andreas Organs (the son)

<

<

French Organbuilding Cavaille-Coll

The photo is the 1864 Aristide Cavaillé-Coll organ in Moissac abbey (France). The case dates from the mid 17th century.

- Ardennes, GIVET, Église Notre-Dame, C-C 1868

- St Jean Baptiste de Long, Somme, C-C,1877

- Saint-Sulpice, Paris, Thesis & scales, Jesse E Eschbach III

- Lucon Cathedral, C-C 1852-57 plans & scales

- St Omer, C-C, scales

- Paris, ND des Champs, c-c 1877, drawing and scales

- Jesuskirkens, Copenhagen, C-C - 1890.pdf

- Experiments on Organ Pipe lengths - Cavaille-Coll

- Notebook by Cavaille-Coll, Aristide, 1811-1899

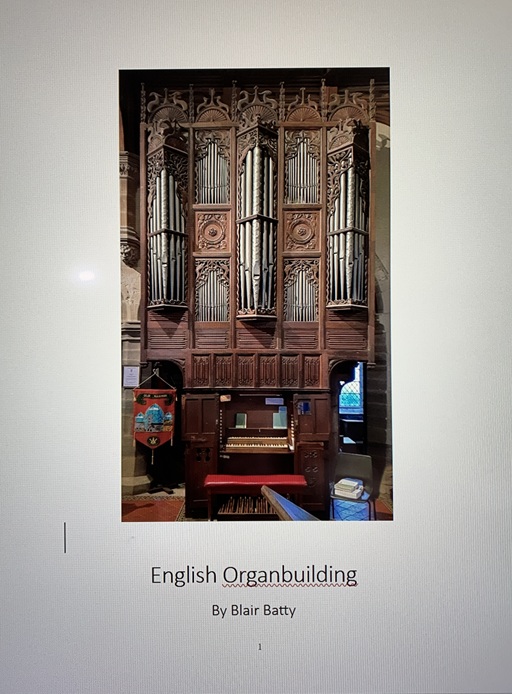

English Organbuilding my book

This PDF is some of my personal notes about English organs.

It also contains information send to me by friends, as well as information from various books and publications. Much of it I wrote down decades ago. I’ve ignored history, which is well covered by others. It’s been three decades since I’ve heard the organs, so I’ve refrained from discussing what they sound like. There are excellent commercial recordings of historical English organs, with appropriate repertoire played authentically.

I also ignored construction and mechanism, which at the time I felt we were already doing better. Mostly, I was interested in how the stoplists and pipework evolved over the centuries; and how the pipework was constructed and voiced. I’ve documented pipe measurements, which is interesting to organbuilders, and difficult to obtain.

- My Book on English Organbuilding

- Willis Oboe boots, ACAD file

- Hill Gt & Ch chest layout ACAD file

- The Englishness of the English Organ - Thistlethwaite

- Dictionary of Organs and Organists - 1921

- Harris organ in Guimiliau, 1676

- Old Radnor Case, 16th Century

- Fr Smith organ, 1698, Gt St Marys, Cambridge

Contemporary Organbuilding Examined Organs

This is an assortment of organs of the past century, that I've examined. Selection was according to availability (e.g. we were cleaning the organ, so had intimate access to it), rather than because it was exceptional...

Some Modern Organs- 1961 Casavant (early Phelps)

- Lots more to come...

- Lye Brochure and Opus list

- Lots more to come...